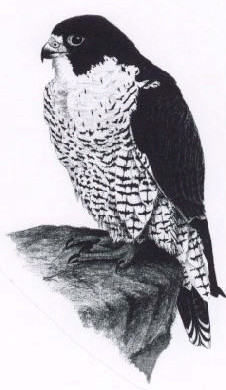

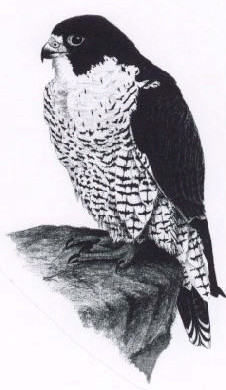

Story and drawing by Paul Donahue

The Peregrine Falcon (Falco perigrinus) is one of six species of falcons found in North America and the largest of the three species that nest in Maine. For many, the Peregrine is the ultimate bird of prey -- elegantly- plumaged, sleek, graceful, a superb and at times extremely fast flier, and deadly efficient at capturing on the wing the birds and bats that comprise its prey. Peregrines are medium-sized raptors, roughly the size of a crow, with a long tail and long, pointed wings. Adults are a slate-blue above and white finely barred and flecked with black below. In wild settings they generally prefer high cliff ledges as nesting sites, from which they have a commanding view of the landscape. In more urban settings they adapt well to high ledges on tall buildings and bridges.

The Peregrine Falcon is the most widely-distributed bird of prey species in the world, with races nesting on every continent except Antarctica. Here in North America we have three races of Peregrine. Tundra Peregrines nest in Greenland and across the arctic and subarctic regions of Canada and Alaska. In the winter, individuals of this highly migratory race travel south to the Caribbean, Mexico, Central America and South America, as far south as Argentina and Chile, with many passing along the Maine coast in their journeys back and forth. Darkly-plumaged Peale's Peregrines are sedentary inhabitants of the wet Pacific Coast of British Columbia and southeastern Alaska.

American or Anatum Peregrines were the race that historically nested in the Maritimes, throughout much of New England, southward in the Appalachians, in the upper Mississippi River Valley, and throughout mountainous areas of the West. In Maine this race was historically found nesting in the interior mountains and on coastal headlands. Studies in the 1930s and 1940s estimated about 500 breeding pairs of Peregrines in the eastern United States and about 1,000 pairs in the West and Mexico.

Unfortunately, however, Anatum and Tundra Peregrines began to suffer a devastating decline in the 1940's, shortly after the introduction of the pesticide DDT.

The Peregrines accumulated DDT and its breakdown product DDE in their tissues from eating birds and bats that had eaten DDT- contaminated insects or plant material. These toxic chemicals then interfered with eggshell formation in the falcons. As a result, the falcons often laid thin-shelled eggs that broke during incubation. Too few young were raised to replace adults that died, and Peregrine populations seriously declined.

By 1962 the Peregrine had been extirpated as a nesting species from all of the eastern U.S. Although the decline was less severe in the West, by the mid-1970's populations there had been reduced by 80 to 90 percent. Only Peale's Peregrines nesting along the north Pacific Coast appeared to be stable.

Partly because of the decline of Peregrines, as well as Bald Eagles, Ospreys, Brown Pelicans and some other large birds, in 1972 DDT was banned for most uses in the U.S. Then in 1974, as part of a cooperative effort among The Peregrine Fund, state wildlife agencies and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, scientists began releasing captively produced young falcons back into the wild. Since then, as part of reintroduction efforts, more than 4,000 Peregrines have been released to their former habitats. Here in Maine, restoration efforts began in 1984, and breeding Peregrines were re-established in 1987. Populations of Anatum Peregrines are now estimated to be about 1,200 breeding pairs in the lower 48 states, with eight pairs having nested in Maine in 1997.

While the recovery effort has been very successful and Peregrine populations seem stable today, we should be aware that DDT is still allowed as an '"impurity" in some pesticide products sold in this country. More importantly, the U.S. manufacturers of DDT have been allowed to continue shipping the pesticide to many Latin American countries where Peregrines and their prey spend the winter. Moreover, many other chemicals still in common use have the potential for causing similar sorts of reproductive problems in birds of prey. Hence, the future of this great bird of prey is still not secure.